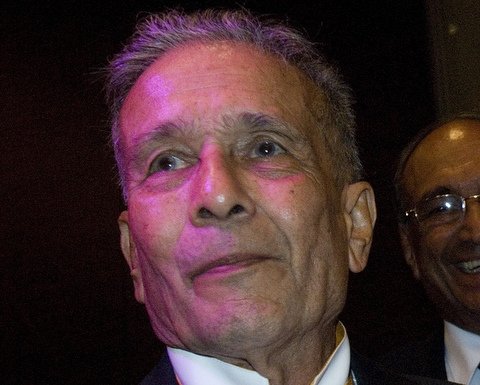

In recounting the history of the Sri Lankan plantation industry, there are numerous examples of industry veterans whose work made vital and lasting positive contributions to the industry, and the people whose lives are directly and indirectly connected to the planation sector. Prominent among such contemporary planters is the locally and internationally renowned Dr. Dan Seevaratnam.

Having officially retired in 2014 following a storied 40 year career at some of Sri Lanka’s leading Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) Dr. Seevaratnam developed highly specialised expertise in the country’s primary crops, and is still remembered as an individual who prioritized the welfare of his employees as an essential pre-requisite to performance, earning him the moniker ‘the People’s Planter’.

Working in the industry throughout its shift from state-controlled management into the era of privatization, Dr. Seevaratnam was a pioneer in developing a new, more inclusive plantation model that focused on the improving quality of life through systematic interventions combined with a successful, sustainable business model. However, among Dr. Seevaratnam’s most notable accomplishments was his role in championing concerted diversification into the oil palm sector.

“One of the biggest problems that we faced, even at that time was the acute shortage of labour. Given the labour intensive nature of the majority of Sri Lanka’s plantation crops, this shortage was a real issue. People were leaving the industry; and with good reason. Though tea was a reasonably profitable crop, there was no way for us to continue it in the low country and rubber had been a non-starter for many years. So from a purely business perspective and keeping in mind the labour dynamics, oil palm was the most viable crop for our investment, and I believe that is still strongly the case today,” Dr. Seevaratnam explained.

A highly lucrative crop that has become increasingly ubiquitous in modern times, oil palm is a popular edible vegetable oil that is regularly used for food preparation across the globe, and is also commonly used in the commercial food industry, and in cosmetics and a wide variety of consumer goods.

Given the commodity’s increasing usage, global demand for oil palm continues to rise, with approximately 64.5 million tonnes of palm oil was produced globally in 2016. Collectively the global palm oil market’s value is projected to continue to expand from US$ 65.7 billion up to US$ 92.8 billion by the year 2021. Meanwhile, from a production standpoint, oil palm is the world’s most efficient crop.

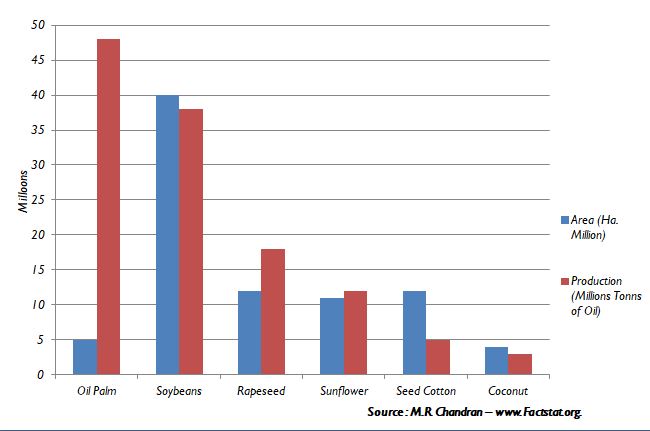

He noted that soya bean oil, the closest competitor to palm oil, accounts for approximately 29.8% of total vegetable oil production however, as a crop, Soya Bean requires the largest land area – approximately 103.8 million hectares of cultivated land or approximately 58.4% of the global land extent under vegetable oil crops, in order to produce 41.8 million MT annually. Canola accounts for 24.4 million MT produced from 33.3 million hectares or 18.7% of the global land extent under oil crops while Sunflower oil accounts for 14.6% of such land, but produces 10.5% or 14.8 million MT per annum.

In comparison, Oil Palm far outstrips any of its competitors, producing 59.4 million MT or 42.3% of the total global requirement for vegetable oil – using just 14.8 million hectares of land which is just 8.3% of all land across the globe used for cultivating crops for vegetable oil.

While Sri Lanka’s first oil palm plantations were established in the late 1960s, Dr. Seevaratnam’s involvement in the sector represented a radical step forward for the Sri Lankan oil palm industry. During his tenure as CEO at Namunukula Plantations, Dr. Seevatratnam oversaw the planting of 1,000 hectares of oil palm in the Matugama region, and was also involved in the establishment of 7,000 hectares of oil palm in West Kalimanthan, Indonesia, and later spearheading the highly successful diversification efforts of Watawala Plantations, which at the time, already had established oil palm cultivation.

“During my career as a planter, there were certainly many points which I look back on with pride, however as far as I’m concerned, our greatest achievement during my time as a Planter was not in turning around unprofitable companies, but in the rapid turn-around in the quality of life of the estate communities which I worked with; and this is keeping in mind that when I retired from Watawala Plantations, it was making the highest profits from any of the RPCs.

“The year I left, we had 15 international, regional and local awards. But that is not what I’m most proud of. Seeing this community, and the amazing transition in terms of quality of life through their hard work, that is something which I will continue to look back on with pride, and I can state with full confidence that this remarkable transformation would not have been possible without our diversification into oil palm”

In that regard, Dr. Seevaratnam advocated for continued support towards the further expansion of sustainable oil palm cultivation in Sri Lanka as an ideal vehicle for promoting the socio-economic development in Sri Lanka. He based his argument on three fundamental factors: the economic benefits to the country through the substitution of imported edible oils; the potential for improvement to livelihood and quality of life for workers; and the overarching impact that such improvements would have on strengthening Government revenue collection by broadening the income tax net.

“Oil palm is probably the only commodity crop in Sri Lanka where the worker is paying income tax. You can compare this with paddy and tea, where workers who engage in these crops rarely – if ever – earn sufficiently to fall into the tax bracket. Meanwhile both of those sectors result in enormous drains on Government revenue in the form of various subsidies,”

“Unlike the garment factory where probably half to 60% of value addition is on imported material, with plantation crops like oil palm, apart from the seed material, everything is locally grown and it is all completely locally owned from the plantation to the to the mill and this is a huge advantage for the country if we can take a strategic approach,” Dr. Seevaratnam explained.

Lack of awareness the main obstacle to oil palm cultivation

When asked about whether he had faced significant resistance to the cultivation of oil palm during his tenure as a planter, he noted while there had been obstacles, the majority of problems had arisen out of a lack of proper awareness about oil palm, and its potential for social development.

“As you may know, change in any form entails resistance in this country and unfortunately, oil palm has not been an exception. This can become a serious hinderance to development and during my time there were instances where gangs had gotten onto the estate and slashed plants in the nursery and even those working on the estates. A lot of this resistance stems from the characteristics of oil palm as a crop and the established cultures that have developed around the main cash crops like tea and rubber.”

To illustrate his point, he cited the customary practice established among rubber tappers where latex that dripped into the coconut shells used for tapping rubber overnight; colloquially known as a ‘cup lump’. While legally the property of the companies, this cup lump is often taken at night by those living in nearby villages for sale at a price of around Rs. 200 per kg.

“When rubber is replaced with oil palm they tend to feel that this small bit of income is also being taken away from them, and they don’t understand how this crop will benefit not just those working on the estates, but also the surrounding regions. I have personally witnessed this transformation at an advanced stage in Indonesia and Malaysia and in its earlier stages in places like Udugama. This is why it is imperative that we conduct awareness campaigns, and show these people just how much of a positive impact that oil palm cultivation in improving the prosperity of a region,” Dr. Seevaratnam stated.

He stated that in many instances, when these types of cultural biases were combined with well-meaning but ultimately misinformed or completely false perceptions about the environmental impact of oil palm that resistance to its cultivation tended to emerge.

“It is unfortunate that this negative perception of oil palm has come about. It’s difficult to ascertain a single cause for it; there are all types of ideas being aired as to water consumption and fertilizer use, but what these people fail to grasp is that this is one of the world’s most efficient plantation crops. It uses a little more resources than rubber to produce a crop that is exponentially more valuable. If managed with proper agronomic practices, there is absolutely no reason why oil palm cannot be cultivated in a socially and environmentally sustainable manner. I believe the first step should therefore be to conduct sensitization programmes in areas ear-marked for cultivation.

“By explaining to these people the true picture of oil palm; that in actual fact is not harmful for the environment when proper practices are followed, and that they can drastically improve their livelihood, and enjoy unprecedented economic development for themselves and for their region, I think people will be more cooperative. We must work together with all stakeholders to bring about such a result.” Dr. Seevaratnam stated.

A lucrative harvest leveraged for social and economic development

Elaborating on the remarkable development enabled by oil palm cultivation, Dr. Seevaratnam explained how in parts of Malaysia that had been embarked upon oil palm cultivation, the standards of living had rocketed up for those in the area – as evidenced by the construction of schools, machine workshops and an entire micro economy centered around oil palm.

He pointed to similarly transformational examples of development in the Udugama region following the successful establishment of oil palm cultivation.

“A simple way to understand just how drastically the lives of these people who actually live in close contact with these plantations has improved, is to do a quick socio-economic survey and compare with areas of rubber cultivation. The difference is like chalk and cheese. If you visit a cooperative shop in the Nakiyadeniya estate, they now stock products like Sustagen and Nestomalt, and Sensodyne toothpaste.

Caption: One of the largest motorbike showrooms outside Colombo is in the Udugama region

While Sri Lanka currently has 8,500 hectares of land being utilized for oil palm cultivation; all of which is managed by 4 of the island’s regional plantation companies while the Government has set out a target of 20,000 hectares of oil palm cultivation. More RPCs are now embarking on their own diversifications into the oil palm business, replacing, most often through the replacement of unproductive rubber crops.